Difficult Knowledge: The Labour of Listening

Observing the work of Rebecca Belmore, an interdisciplinary Anishinaabekwe artist, and one of Canada’s most important contemporary artists[1], engages the viewer in a labour of listening. Experiencing Belmore’s work is a sensory experience that envelops the entire body.

Difficult to Ignore

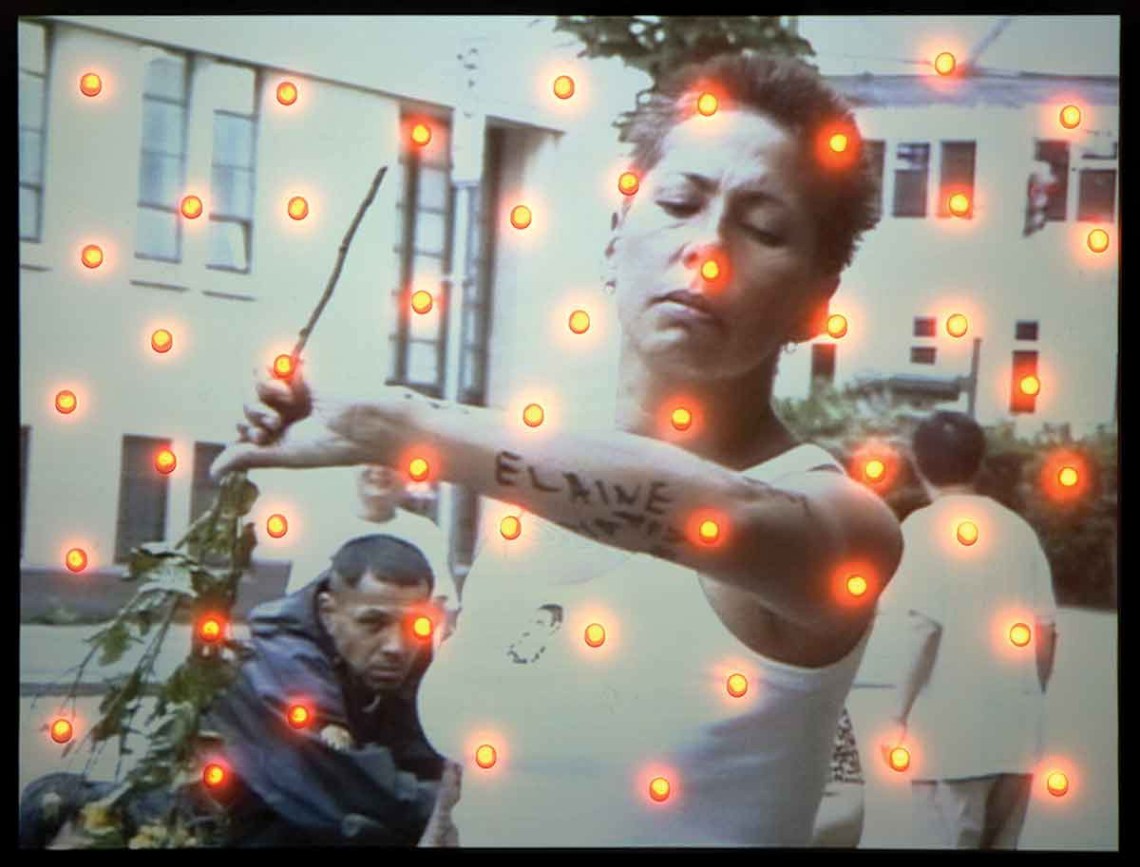

It is difficult to deny the feelings that overtake us upon experiencing a performance piece like Vigil, which Belmore begins by ritualistically cleansing the area, on her hands and knees. This action appears useless on an outdoor sidewalk, which will never be fully clean, a ritual Belmore chooses with intention on multiple levels. After lighting commemorative candles, she repeatedly nails her red dress to wooden posts in the downtown Vancouver area of the abductions of many missing Indigenous women. She then laboriously pulls herself away from the post, leaving pieces and threads of her dress behind. After a considerable period of time, Belmore stands silent and exposed in her underwear, her dress left behind in shreds, reading the names of the missing women written on her arm. She then voices them, one by one, yelling them into the air, as if to reach the women themselves, and strips the thorns off of a rose through her clenched teeth after each woman is named.

At times I found the rawness of this performance difficult to watch, but the real work (and it seems there is little as a viewer, comparing to the artist) is in processing the work. The affective labour involved in this in an integral part of difficult knowledge and of its attainment in a visual culture.

To go there with Belmore is to respect her as an artist, the vision she has and the message she is striving to communicate. As a non-Indigenous individual who has benefited at the expense of the Aboriginal community by colonialist attained land ownership, educational systems, and so much more, it is my responsibility to listen and to feel, rather than to look away or walk away. Belmore in fact : “recognises, and asks her audience to recognise as part of a shared history, that continued colonialism is why more of the disappeared women are unnamed than named. Belmore performed because she was haunted by 65 women or more, named and unnamed, who were ghosts before they were really ghosts.” [2]

Artist Rebecca Belmore listens to the sound of the landscape at Green Point through Wave Sound.

Artist Rebecca Belmore listens to the sound of the landscape at Green Point through Wave Sound.

Listening is all that Belmore asks of the viewer. Whether listening to the land, as she asks us to do in the creation of her 2017 body of work titled Wave Sound, situated in several locations across Canada, or listening to her voice the names of the nameless women who have disappeared across Canada. Active listening helps us access the difficult knowledge that we have trouble accepting, or the feelings we may not wish to acknowledge, but in the case of showing allyship, it is necessary.[3] Unearthing the difficult knowledge, accessing it, acknowledging the emotions that loss, death and the aftermath of these difficult experiences requires labour. Labour that artists like Rebecca Belmore challenge us to take on, by asking us to take on not only the viewing of their work, but by thrusting upon us the aftermath of the emotional processing.

As Simon contends in his article on Difficult Knowledge: “To speak here of the courage to (and responsibility of) witness is not nearly enough.” however “To witness in a manner that opens the possibility of altering the existence of that to which it bears witness requires a dialectical coupling of affect and thought, implicating the self in the practice of coming to terms with the substance and significance of history.”[4] After all, as educators, artists, or even simply art viewers and humans, isn’t that the very least that we can do?

[1] https://ago.ca/exhibitions/rebecca-belmore-facing-monumental

[2] Maggie Tate (2015) Re-presenting invisibility: ghostly aesthetics in Rebecca Belmore’s Vigil and The Named and the Unnamed, Visual Studies, 30:1,

[3] Wendy Ng, Syrus Marcus Ware & Alyssa Greenberg (2017) Activating Diversity and Inclusion: A Blueprint for Museum Educators as Allies and Change Makers, Journal of Museum Education, 42:2, 142-154

[4] Simon, R. (2011). A shock to thought: Curatorial judgment and the public exhibition of ‘d_i_f_f_i_c_u_l_t_ _k_n_o_w_l_e_d_g_e_’._ _Memory Studies, 4 (4), p 446.