Memory and time are often constructed through the viewing of imagery and photographs. Our personal experiences and moments of historical significance are frequently formed by frozen images, narrated by historians, scholars or even individuals. The choice of what gets presented to form a narrative of historical significance is something that has surfaced in my mind through the readings and images discussed in this blog post.

Cheryl Thompson, a professor at Ryerson University, argues that the representation of Black Bodies in photographic history and the role of photography in producing black identity/imagery is one of surveillance, of being watched.

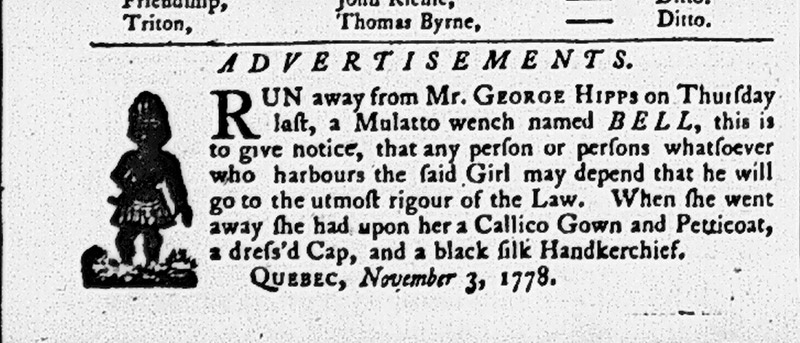

Her words brought to mind a photographic series Wanted, by artists Camal Pirbhai and Camille Turner displayed at the AGO and around the Eaton Centre shopping district. (http://ago.ca/RewardWanted) http://camilleturner.com/project/wanted/ To construct these images, the artists used text from actual 18th century Canadian slave ads, describing in detail the apparel worn by slaves who had run away, to reposition the Black subject in the present.

I was shocked to read these advertisements and learn about this part of Canada’s story. In Canada’s history, we cling with pride to the Underground Railway; however, what is often ignored is the long history of slavery that remained and the escape of many Canadian slaves to the United States before the British abolished slavery in their empires in 1843. “When you had Confederation in 1867, and a new narrative of the country was being written, [slavery] was one of the narratives that was forgotten” explains historian Afua Cooper.[1]

By using the wording from Canadian archives of advertisements for runaway slaves and representing them as fashion models in contemporary advertisements, the artists reclaim the photographic subjects. The images give the viewer the sense of empowerment of the subject in a way that the Black Body is not seen as contained or imprisoned, rather as having the liberty to make their own choices, while still maintaining the setting of the urban contemporary.

Camal Pirbhai and Camille Turner, Bell (Wanted Series)

The model in this work gazes outwardly at the viewer, owning the frame, while casually posing using a weathered Bell Canada payphone, a relic of one of Canada’s most powerful companies, ironically sporting the name of the escaped slave. The urban containment of the black subjects pictured in Northern cities that Cheryl Thompson described as typical is evoked in these images as they suggest nostalgia of the Harlem Renaissance, bringing together past, present and possible future. Camille Turner’s desire to “un-silence the stories of the people of African descent who arrived here before”[2] is truly evident in these pieces, which give voice to a new narrative.

A New Herstory of the Black Female

Kimberly Juanita Brown, in her book, The repeating body: slavery’s visual resonance in the contemporary, argues that what is needed is an exploration of the ways that artists are resisting imagery that only exposes the trauma of Blackness. Many artists, she contends, expose “the impossible duality between black women’s representations and slavery’s memory”[3]. Wanted, through its empowerment of the black subject, and the creation of a new narrative, resonates with Brown’s arguments. The imagery in these photographs has evolved, while still paying homage to historical chronicles, expanding the notion of female icons Brown references as “stagnant” or frozen in time in their visual representation.

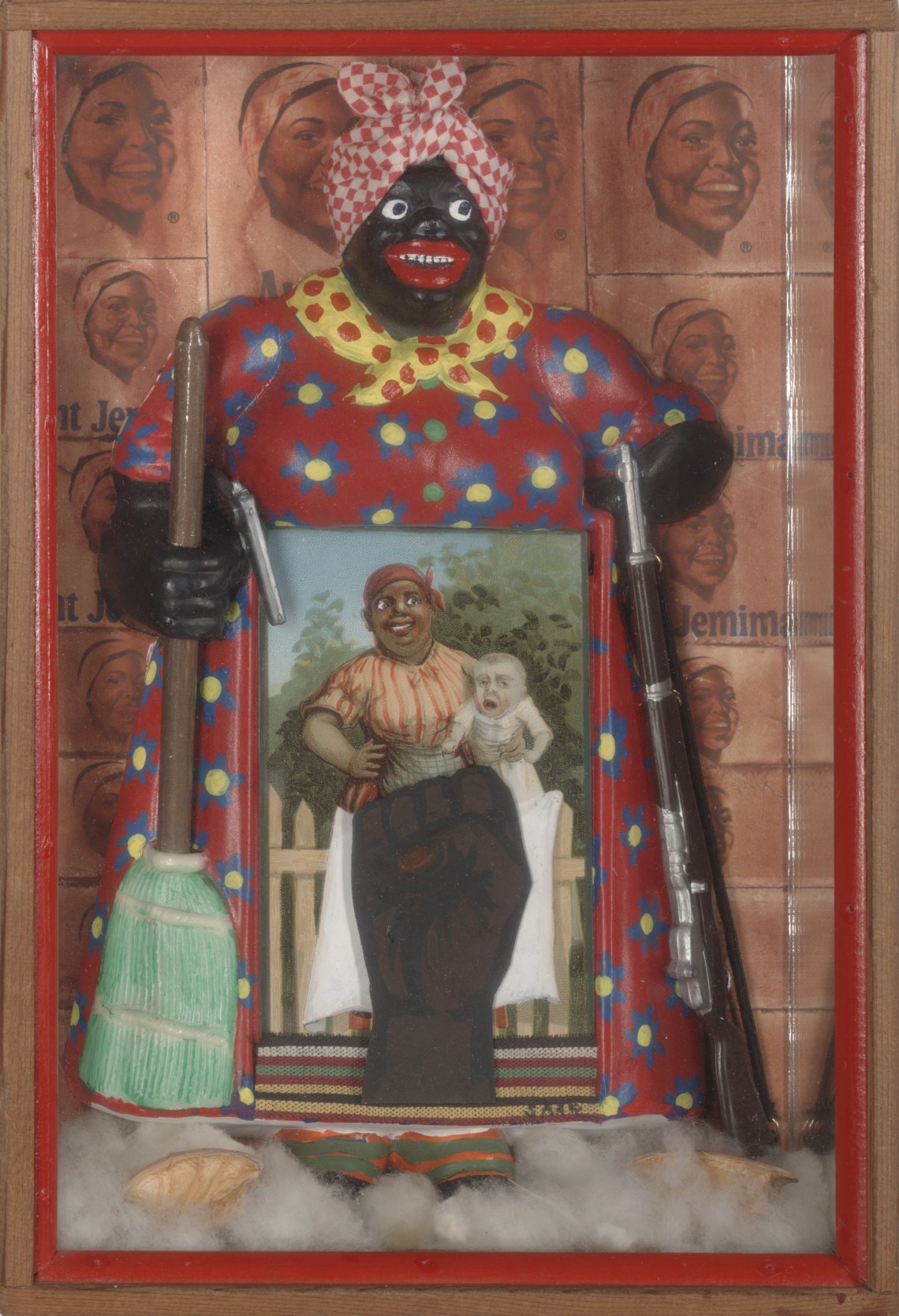

Betye Saar, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, 1972. Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, California. Photo by Benjamin Blackwell. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts & Tilton, Los Angeles, California.

The Wanted Series furthers the work of Betye Saar, who as early as the 1970’s took racist and stereotypical representations of Aunt Jemima, with her “layers of asexuality and maternity” and transformed them into symbols of power. Liberating Aunt Jemima by equipping her with the tools of a soldier and playfully juxtaposing domestic tools alongside the tools of a fighter serves to empower her to liberate herself as well as many black female viewers from the shackles of their historical portrayal.

The consideration of memory and time, how it is constructed and portrayed has reshaped my own vision as an art educator. To include images such as the ones examined in this blog is part of my desire and responsibility, especially as an educator in an all boys Independent School, itself being in a place of privilege.

[1] The Hanging of Angelique: The Untold Story of Canadian Slavery and the Burning of Old Montreal, [1]

[2] http://ago.ca/wanted-essays

[3] The repeating body: slavery’s visual resonance in the contemporary, Duke University Press, 2015, pg3